‘It is a monotonous refrain to say that we need to occupy our country, own the land, march westward, turn our backs to the sea, and not remain eternally with our eyes fixed on the waters as if we were thinking of leaving…The founding of Brasília is a political act whose scope cannot be ignored by anyone. It is the march towards the interior in its fullness. It is the complete possession of the land. We shall erect in the heart of our country a radiating centre of life and success.’

- President Juscelino Kubitschek, quoted in Revista Brasília 40:79 (1960).

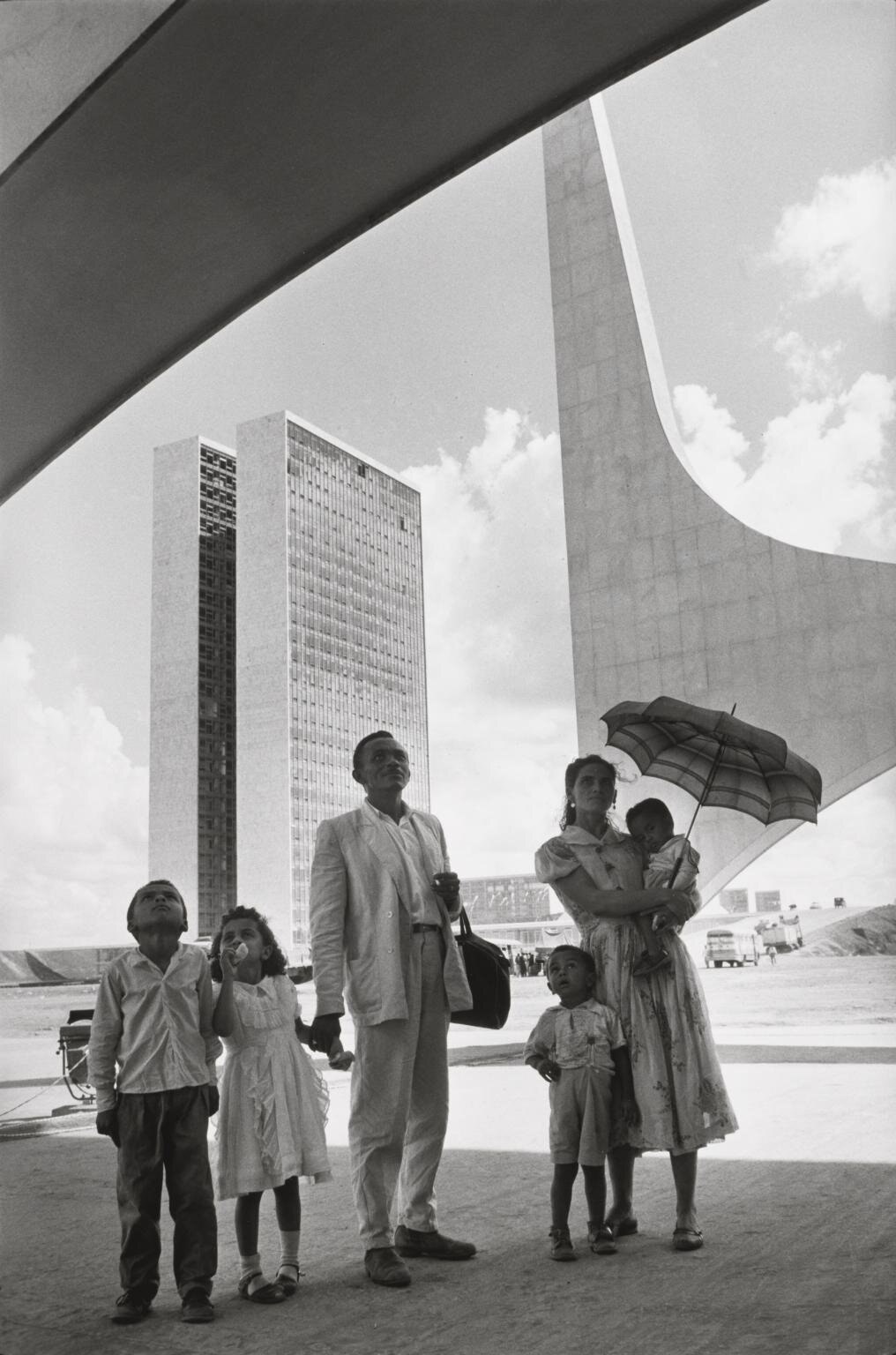

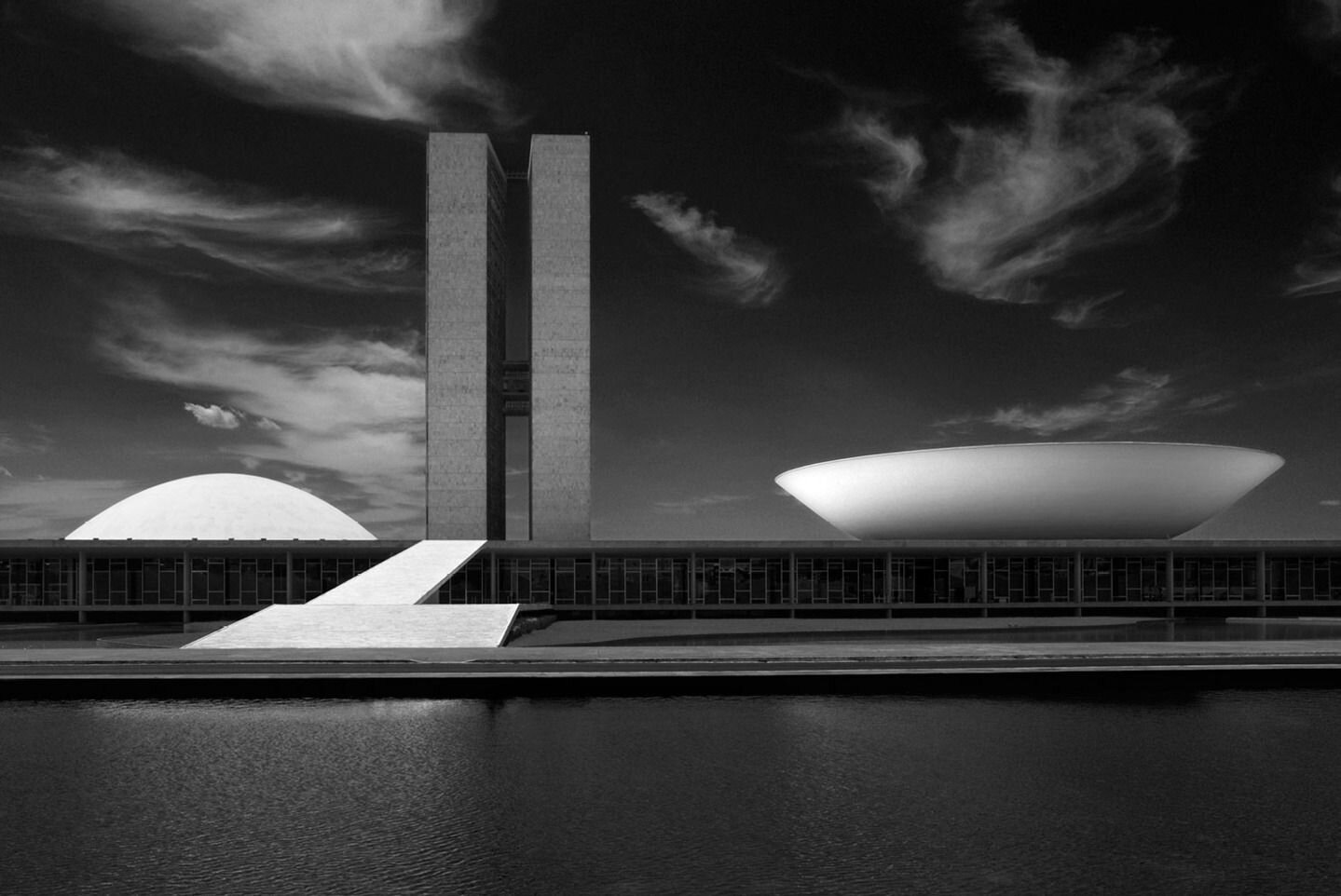

Photographs by Marcel Gautherot in the magazine Aujourd'hui Art et Architecture, July 1964.

Brasília is presented here in just the way its boosters intended: a space-age enigma, an extension of the possible. Of all the photographers working on the site in the early years, Marcel Gautherot was particularly adept at conveying the strangeness of Niemeyer’s buildings, which eschewed straight lines and angles for ‘free-flowing, sensual curves’. Shapes inspired, the architect wrote in his memoirs, by the ‘sinuous rivers’ of Brazil, the waves of the ocean, even the ‘Universe of Einstein’.

For Niemeyer, Brasília was the ultimate canvas, as well as a vehicle for his communism. His designs have become almost synonymous with the city. But he was only one among a number of charismatic personalities who willed the new capital into existence. For the President, Juscelino Kubitschek, the inauguration marked the start of a new era for Brazil, a ‘stone cast to create waves of progress.’ Transferring the capital from Rio (a constitutional requirement) was first among a list of targets drawn up by his administration to modernise the country and lessen its reliance on primary products. This meant new highways, the cultivation of infant industries, intensified goods circulation.

The city itself would symbolise a vigorous young democracy throwing off the mental shackles of its colonial past. And with its new seat in the central plateau, the federal government could project power into the vast untapped interior. More radically, Brasília was intended as a crucible for a new kind of citizen. The masterplan of Lúcio Costa, a disciple of Le Corbusier, was premised on the conviction that architecture could be a condenser and conductor of change, that it could be used to mould society in desirable directions, propelling the whole nation past undesired stages of its historical development. This meant eliminating capitalist social-spatial stratification and nurturing a modern consciousness through the force of shapes, space, and voids.

Candangos at work, 1970. Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal.

The construction was an epic endeavour, involving thirty-thousand workers, or candangos, recruited from all over the country, though disproportionately from the impoverished north-east. They lived and died in frontier conditions. And with their toil, the city rose from the red earth in just three years - a feat the government worked hard to promote around the world. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, for instance, funded a touring exhibition which debuted at Berlin’s Interbau in 1957 (held under theme ‘city of tomorrow’). Its purpose was to affirm Brazilian cultural renewal, as well as to build momentum for the modernist movement.

The state construction company, NOVACAP, also put together a remarkable journal each month during the construction years, which is full of sketches, maps and photographs. These efforts did much to create a popular impression of the new city, often encapsulated by the bowls of the National Congress, one to signify openness, the other deliberation. Gautherot’s rendition is typical of a mode of representation which glorified form using complementary techniques and perspectives. But there is a deeper context to the above spread, which was published in Paris only a few months after the military coup which brought an end to democracy in Brazil for twenty-one years.

Brasília’s rational layout, broad boulevards and panoramic vistas proved predictably amenable to authoritarian rule. Against the erratic pulse of a port like Rio, it could be patrolled and surveilled with ease. Seen in this light, it’s easy to read into Gautherot’s sullen tones: the great experiment in modernist democracy falling into darkness; the utopian project strangled in its cradle.

Orlando Brito, ‘Soldiers hoist a Brazilian flag on the Planalto Palace’s flagpole’, 1966. A reminder of how quickly things can change, the plasticity of the present.

The military period produced few images that could be described as iconic. In the photographic imaginary at least, Brasília is still defined by the work of a group of photojournalists who played a key role in conjuring a durable impression of a remote place in the late 50s and early 60s. Perhaps the most influential was the great Magnum photographer René Burri, whose work covers the whole spectrum from groundbreaking through to the lived reality until as late as 1997.

Burri’s images of inauguration night are unmatched in capturing the giddy optimism of the moment. I imagine guests stepping out onto the terrace for a moment, breathing in the warm air and taking in the luminous newness of the city. To some that night, it must have seemed like Brasília was just the start, that radiant cities would soon sweep the world, bringing order, control and harmony.

As it turned out, it was the zenith of international modernism. Its failures and contradictions, seeded during construction, contributed in no small part to the movement’s eventual disavowal. Today, Brasília is a microcosm of Brazilian society at large: unequal and spatially divided. Niemeyer’s buildings have lost their lustre, some now plastered with billboards for Netflix shows and the latest iPhone. The paint is cracking, the grass unkempt.

Despite this, photographers still seek inventive ways to render Niemeyer’s curves or integrate them into broader studies of contemporary Brazil. It’s not difficult to see why. Even now, and through a screen, his buildings cast a spell. Who could refuse their twisting forms, especially when set against the spartan solemnity of Brasília at dawn? They do look dated, or at least clearly of another age (‘nothing dates faster than people’s fantasies about the future’, said Robert Hughes in The Shock of the New). But still, somehow, they appear more profoundly modern than anything of this scale dreamt into existence today.

Central to modernist aesthetics was the notion of fresh perception. Some of this architectural work, which is typically abstract and minimal, does succeed in presenting the city afresh. But in continuing a tradition begun with Gautherot, it also reproduces a long faded millenarian discourse - and is therefore at odds with its subject. More interesting is the kind of work which explores what happens when, as Dutch photographer Iwan Baan puts it, the ‘chilly, impersonal drawing from the past’ is populated with real people with complex needs and desires. His work in Brasília and Chandigarh attempts to do this.

It’s also illuminating, and disquieting, to look into the construction archive - although only a fragment of the roughly ten-thousand negatives is available online. As well as Gautherot and Burri, photographers including Alberto Ferreira, Thomaz Farkas, Jean Mazon, Peter Scheier, Dmitri Kessel and Lucien Clergue roamed the site. Taken together, their work preserves for posterity a poignant history of dispossession and repression which has been all but obscured by the ubiquity of the millennial representation.

James Holston’s The Modernist City (1989), an ‘anthropological critique’, provides the classic English-language account of this history. In Holston’s view, planners’ egalitarian intentions were ultimately negated by the ‘inherent paradox of the project itself’ - having to use the old to populate the new (the same tension which Baan confronts). He unfolds the various processes of ‘Brazilianization’ that took place in the city’s first decade, as people reacted to their sterile and uniform environment by reasserting traditional cultural values and forms of commerce. For a number of years, the authorities pushed back. Squatters, chaotic growth and subversive organisations were met with clampdowns and directives. But authorities were defending the purity of an idea which had already been corrupted beyond reprieve.

‘…in compounding the basic contradictions of Brasilia’s premises, [planners] created an exaggerated version - almost a caricature - of what they had sought to escape.’ (Holston: 200)

Vila Amaury, one of the workers’ settlements, 1959.

Early in 1957, the government had run a recruitment campaign for three different purposes (construction, materials supply, and administration). People came from every state in the country, many fleeing a terrible draught. But when the city was deemed complete, the candangos and their families were denied residency rights. In a bid to prevent the Brazil they represented from taking root, authorities set about demolishing the makeshift settlements that had sprung up on the ‘semi-legal periphery’. At least one, Vila Amauary, was inundated during the creation of Lake Paranoá.

In time, authorities recognised that the satellites were there to stay, and most were given legal foundation. But as a consequence, their organic development was stifled as planners restructured them according to the same zoning principles as the Plano Piloto. This essentially meant converting them into dormitory settlements, with residents taking a long and expensive commute to the centre for work. But through such strict separation of functions, the city soon became stratified along class lines.

Elites eschewed the imposed egalitarianism of the superquadras for gated communities on the shores of Lake Paranoá. Meanwhile, everyone except for middle-class bureaucrats clustered in the satellite towns, travelling into the centre only when absolutely necessary, hence the aphorism: ‘In Brasília there is only casa e trabalho.’ In other words, there is a missing third element, a sphere of random congregation and celebration which in other Brazilian cities is the street, the square or the beach.

Marcel Gautherot, Sacolândia, c. 1958. Acervo do Instituto Moreira Salles, Rio de Janeiro.

The origins of this dual order can be encountered in Gautherot’s documentary work in Sacolândia, the most basic camp in the federal district. It was named for the old cement sacks people used to line their shelters. Whereas much photojournalism of the time presented the candangos heroically, these images reveal the underlying reality: families eking out an existence from the detritus of construction, having been promised a new start. The photographer later spoke of wanting to publish a book on Sacolândia. But he was unable to find a publisher.

As much as Brasília has failed to realise its utopian promise, its physical profile has also been softened by urban sprawl. Designed for half-a-million people, the metropolitan area is today home to more than four million. It’s likely Costa would have considered this an unacceptable subversion of the project’s integrity. After all, his proposal was selected for its fundamental rigidity: his capital would be self-contained, closed.

And yet when touring the city on Street View, I began to appreciate how the masterplan is not really legible anyway. There is a sense of Brasília’s scale, of the negative space. But the overall vision is inaccessible, at least from the inhabited perspective. If you ascend to the viewing deck of the Torre de TV, something approaching a general overview can be found, however. Visitors can look straight down to the Praça dos Três Poderes along the Monumental Axis, which, with its twelve-lanes, holds the record for the widest central reservation of any dual carriageway in the world. A strange way to think about the strip of land on which all of Brazil’s most powerful institutions are based.

Twenty kilometres from the centre is the Torre de TV Digital, Niemeyer’s last building. It’s fitting, perhaps, that the great architect bowed out with a means to gaze upon his works. The viewing deck offers a more comprehensive, but still dissatisfying view of the modernist city.

The Torre de TV, 1968. The Energetic Church believes the structure is one of the foci of Brasília’s mystical energy. The city is home to an array of New Age, paranormal and occult groups, many of whom hold that it was built upon the world’s largest crystal deposit. At the Temple of Good Will, there is a pyramid capped with a huge crystal.

The only way to fully appreciate Costa’s intentions is from the air. Brasília is intimately tied to the concept of flight, most obviously through its outline. For Le Corbusier, planes were the ultimate symbol of mechanical civilisation, of the new age. In them, planners could fly over the great cities of the nineteenth century, crammed and haphazard, and derive immediate insight about what to raze, what to keep, where to develop. And with such capacity, the underdeveloped world could avoid the chaos and inequity of the Industrial Revolution. As he put it in Aircraft (1935):

‘The airplane has given us the bird's-eye view. When the eye sees clearly, the mind makes a clear decision.’

Aerial view, 1972. The height of military rule.

As the plane banks in the skies above Brasília, its own image stares back. It’s a joyful silhouette, streamlined and buoyant. The sweep of the wings is bisected by the fuselage at a point where Costa placed the city’s huge central bus stop. At the cockpit is the Praça dos Três Poderes. And in the lower promontory, the Alvorada Palace is clearly visible. Bolsonaro’s predecessor as president, Michel Temer, found it to have a negative energy, and vacated.

Although finished for a full twelve years at this point, the city seems somehow still fresh - newly etched and scraped out of the ground. Today, it is somewhat ossified, inscribed by UNESCO as a ‘singular artistic achievement, a prime creation of the human genius’. As such, the fundamentals of the Plano Piloto are protected, frozen - complicating efforts to address Brasília’s chronic problems: inequality, congestion, violence. Adjustments must be made on the periphery of the planned city, in the area designated by Costa as the ‘bucolic sector’.

One of the most significant is an ‘innovation district’ in the north-east designed by Carlo Ratti Associates in Turin. Although the practice claims to have been inspired by Costa, their scheme aims to ‘overcome’ his functionalist divisions and open up the superquadra typology to allow for al fresco dining and landscaped gardens. Grafted onto the tip of one of Brasília’s wings, the district will a new layer of historical meaning to the city, testifying to an age of starchitects, environmental rhetoric and private-led development.

Plano Piloto, Google Street View.

Elsewhere, a kind of synthesis between Kubitschek’s vision of national self-aggrandisement and the smart city movement is being carried out on a much grander scale. The Indonesian government recently announced plans to transfer the capital from Jakarta to a new ‘forest city’ on Borneo. As with Brasília sixty years previously, it’s partly about escaping colonial legacies, as well as national self-assertion.

But Nagara Rimba Nusa (‘forest and island hilltop’) will be based on very different ideas: a blend of Indonesian spiritualism and twenty-first century eco-connectivity. The city will be networked and compact, with private vehicles discouraged. And it will supposedly manifest a spatial philosophy based on a harmony between people, God and nature. The architect, Sibarani Sofian, has even spoken of realising a concept of ‘bio-mimicry’ which seeks to ‘imitate and adapt the forest into a man-made development’.

The official justification for the move is that Jakarta is sinking, a legacy of Dutch mismanagement, population growth and the over-extraction of groundwater. To combat this and keep the ocean at bay, a forty-kilometre sea wall is being built, its massive cost to be partly offset by selling prized real estate on the reclaimed land. An artificial island will form the shape of Indonesia’s national symbol, a mythical eagle known as Garuda Rakasa. It will be quite a sight from the air.

Meanwhile, the largest purpose-built capital in history is rising rapidly in the Egyptian desert. Recent drone footage shows the astonishing speed of development. The decision to move was only taken in 2015, a year after the military coup which brought Abdel Fattah El-Sisi to power. Many of the new government buildings are complete, and the residential districts have taken final shape. From above, they look a bit like a motherboard.

Planners claim to have learned lessons from other city-building projects, and say they are not setting out to build a ‘monumental’ city. Instead, the New Administrative Capital will be ‘smart’ and ‘sustainable’, with satellites being used to monitor traffic and optimise circulation. Residents are to carry a unified ‘main card’ to access goods and services. There will be an entire entertainment sector, and a ‘green backbone’ twice the size of Central Park. The CBD will feature the tallest tower in Africa, an odd pyramidal structure meant to demonstrate continuity with ancient civilisation.

Residential districts under construction in Egypt’s New Administrative Capital, with the CBD cluster visible on the right.

Just as Brasília is seen by some as marking the beginning of intensive deforestation in the Amazon, the new capital on Borneo is only the latest landmark in a long history of efforts to master the resource-rich interior. And in an echo of Naypyitaw (built by the Mynamar military at the start of the century), Egypt’s new capital will go a long way to insulate the Sisi regime from protest. The prospect of another Tahrir Square in a city of bureaucrats seems remote.

Both schemes stem, ultimately, from a will to evade the symptoms of modernity. The megacities of Cairo and Jakarta have become unsustainable, liabilities - their ‘circulation clogged’ and ‘respiration polluted’, to use Holston’s words. Le Corbusier would have called them unhealthy organisms. But behind the shiny visualisations is the same old dysfunctional lurching: the displacement of risk, a technical fix to slow-burn crisis in a conjuncture increasingly defined by the spectre of climate emergency.

And the new cities will not be hermetically sealed. Given time, their inner contradictions will work themselves through, leading one day, perhaps, to the renunciation of their organising principles. Planned capitals are supposed to interrupt the disorderly cascade of events. The masterplan for Brasília mandated a certain fixity of form, as though to cement the country’s self-image in 1960. But the course of things runs on, delivering shocks and sudden reversals, introducing maladies and contradictions which cannot be resolved without recourse to the kind of practices utopia forbids.

I wonder about the images these early twenty-first century mega-projects will leave behind. The golden age of photojournalism is long gone, and with no symbiotic relationship prevailing between the medium and a movement such as modernism, there is no real imperative for architects, planners and artists to collaborate. It seems unlikely there’s a René Burri or Marcel Gautherot at work down there, documenting the suffering and sacrifice. So perhaps the best we can expect is a drone flyover.

Dmitri Kessel, 1961. LIFE Photo Collection.