‘Nothing can remain immense if it can be measured.’

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (1958)

Hannah Arendt’s words have particular poignance for an age in which the entire planet has been measured, mapped and simulated. We know the contours of every island, their relative size, the depth of every lake, even the rough trajectory of continental drift. Within two-hundred million years, the familiar landmasses will have crunched back together again to form a new supercontinent: Pangaea Proxima.

Such thinking is so deeply naturalised that psychologists and geographers speak of perceptually salient features being copied into the mind like a map (the ‘cognitive’ approach to orientation). Against this, an anthropological approach emphasises that places do not so much have locations as histories. People do not ‘navigate’, but wayfind. Without the map, the world has no contour, form, or limits. It is just the world.

This idea is something alien to us moderns, so entrapped in a mode of thought which separates humans from ‘nature’, subject from object. With our capacity for ‘whole earth observation’, epitomised by the famous Blue Marble image, the world has been shrunk into a ball, its basic contours as familiar as an iconic logo. Google Earth is one of the most significant products of such dualist thinking; an intensification of its analogue antecedents: physical globes by which continents are mapped perspectively onto a spherical surface made variously from hides, papers and plastics.

But while the latter are inherently ‘global’ in Dipesh Chakrabarty’s (2021) sense (humanist; encompassing histories of state consolidation, dialectics of empire and capitalism), the former aspires on a fundamental level to embody the ‘planetary’ - a category which decentres humans. However, this objective cannot be reached and will remain forever elusive. Google Earth can be seen as a fetish object, the psychological equivalent of a synecdoche, by which a part (the idealised surface) is made to represent the whole: Gaia.

This is crucial in the age of the Anthropocene. Not only were humans never separate from nature, it is becoming increasingly difficult to clearly differentiate so-called natural shocks from the symptoms of ‘our’ cumulative actions. Such circumstances have profound implications. And there is a wealth of literature in anthropology, philosophy, science studies addressing them, much of which concludes with a clear imperative: to overcome dualism, cultivate climate-thinking, ecological awareness, planetary social thought and so on.

I want to suggest that Google Earth hinders such awareness, both through its fundamental architecture and more granular properties, by reproducing tendencies towards calculation, oversight and objectification. As a product of one of the world’s most powerful monopolies, the originator of ‘surveillance capitalism’, the program should be regarded with critical scrutiny by default. This is all the more important given the unique success of Google’s public relations strategy. The name is something almost magical, inscribed into the symbolic order as an essential public service in a way that necessarily obfuscates the underlying business model, which returns extraordinary profits.

But my purpose is not so much to critique Google Earth as such, to somehow unveil its pernicious ideological mystifications. Rather, I explore how it exemplifies a condition by which we have lost control of our tools, cast adrift without a compass in a world we thought we had mastered. Google Earth is a product of the ideological condition particular to postmodern culture, whereby there is no Logos (God, History etc) to guide us. It protects us from the traumatic Real of our time: that we are sleepwalking into the abyss, in thrall to the logic of enframing, with no map to show us the way out.

Regimes of historicity: the global and the planetary

Since Google Earth emanates from servers as binary code, beamed to computers all around the world, it therefore ‘exists' in potentially infinite forms at all times. We know then that we are dealing with something very different when Google promotes the program as the ‘the world’s most detailed globe’. Striking in this slogan is the proximity of the three terms (Earth, world and globe), whose meaning it takes for granted. Although used interchangeably and inconsistently in everyday speech, it is worth interrogating these terms. Taken too far, each collapses under the weight of conflicting interpretations.

With respect to ‘globe’ and ‘planet’ (the conspicuously absent term in Google’s formula), an illuminating discussion is found in the work of Dipesh Chakrabarty. His latest book, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age (2021) extends the ideas sketched in ‘Four Theses’ (2009), a seminal intervention in the Anthropocene debate. Reckoning with what Isabelle Stengers calls the ‘intrusion of Gaia into the horizon of human history’ collapses the old distinction between natural and human histories and so requires us to bring recorded and deep time together in our analyses of the predicament and all that led to it. Chakrabarty argues that this means thinking in two ‘distinct registers’ at the same time: planetary and global.

The former is the aggregate outcome of Earth system science, which foregrounds the march of epochs - successive chemical, biological and geological configurations, each giving way under pressure from various shocks, exogenous and not. Chakrabarty’s other category, by contrast, has emerged over centuries through the work of humanist and social-science historians. The ‘global’ is essentially the story of how the Earth as indifferent natural object-realm was converted into a sphere of action for humans, an interconnected global space inseparable from the logics of empire, capitalism and technology. These two ‘regimes of historicity’ operate on radically different timescales.

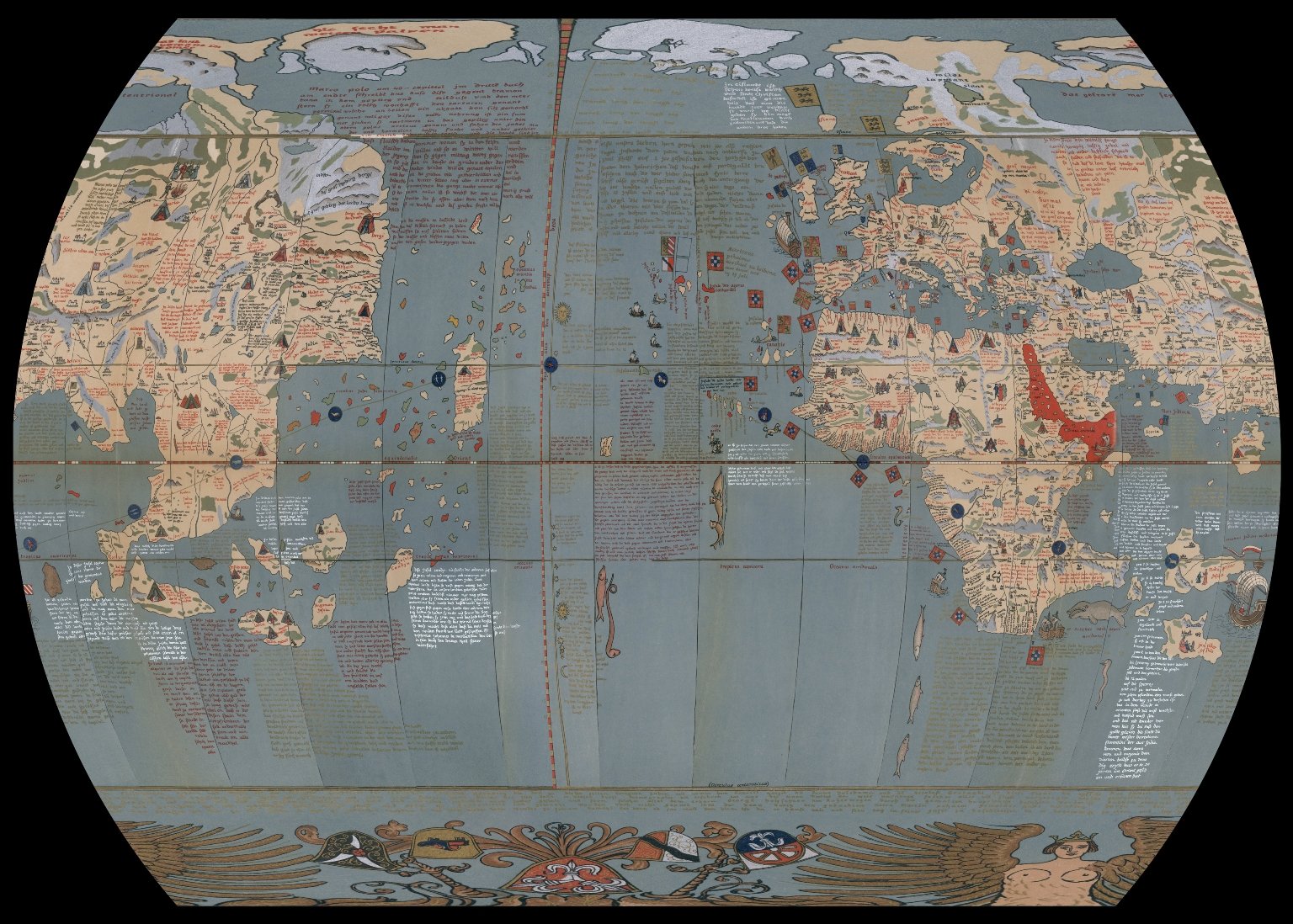

Martin Behaim’s Erdapfel (1492)

Globes in the traditional sense are both productive of and produced by the global regime of historicity in Chakrabarty’s sense, encapsulating the human need to find and stabilise our place in the cosmos. When viewing pictures of historic globes in succession (cf. Sumira, 2014), the viewer is struck by the diversity of idiosyncrasies and mysterious embellishments: whirlpools, hideous sea monsters and personified winds. The oldest surviving example, Martin Behaim’s Erdapfel (1490-92) displays a vast empty ocean between Europe and Asia (Columbus did not return to Spain until 1493), as well as the mythical Saint Brendan’s Island in the North Atlantic. These are products of profoundly different worldviews; mythological and religious thinking. We are left with a scattered material history of fallibility, explicitly provisional and, from our perspective, ultimately failed efforts to map the world.

How does Google Earth fit into Chakrabarty’s paradigm? Only on a first approach should it be read as an outcome of the planetary regime of historicity. Certainly, it represents some kind of culmination of Earth System Science: an assemblage of vast volumes of scientific data generated through various forms of Earth observation particular to industrial modernity, geophysics, geochemistry, geological surveying, ground sensor networks and, above all, satellites. When viewed without superimposed borders, the simulation decentres humans. However, as the next section explores, it is innately ideological. And so, in the final analysis, it falls back into the domain of the global, though in a disavowed, paradoxical manner.

‘I know very well but still’: Google Earth as fetish object

Like all slogans, Google Earth’s cannot stand too much scrutiny. But its central claim nevertheless holds true: the program is the most detailed representation of the planet ever created. Or at least for the inhabited, man-altered surface. All that lies beyond, in the depths of the underlands, the vastness of the oceans, are ignored or inaccessible. The immersive photo-sphere is stitched together from countless satellite images using a technique known us ‘clip mapping’, by which only small regions of graphics - the local area under examination - are displayed in high resolution. This makes possible algorithmic sorting, the selection of relevant data from an otherwise unmanageable volume.

This process of ongoing self-resolution can be apprehended when zooming in or out: once the user stops navigating and the target location is inferred, the continual flustering of pixels is stabilised at a given distance. This is a world unfolding, fixed for contemplation. But it can be reanimated at will, as the user approaches new levels and planes of perspective. Sometimes, wholly contrasting time sets of images are encountered side-by-side: a patchwork of overlapping seasons, bisected by an intrusive mathematical line. Naked, blasted skeletons on one side; a forest of virulent trees on the other. This is the result of data dynamism, and the effect is to dispel any illusion of ‘visual nominalism’ that might prevail. Such failures are an encounter with the Real of the technology - its inherent bittiness.

Viewed from a different angle, the outward expression of clip-mapping in in some sense a technological equivalent to our experience of reality according to the post-Kantian orthodoxy (‘correlationism’, to use Quentin Meillassoux’s term). As humans sense the world, by way of the categories, the brain interprets in a contingent way: what we get is not the Thing-in-itself. As Deleuze put it, consciousness is just a dream while awake. Google Earth in this sense is like a steam-age Mental Processing Unit, not yet sophisticated enough to display phenomena without consciousness apprehending their inherent bitty weirdness, but rather a composite of different sensual ‘feeds’, the result of all manner of technologies (the ‘senses’ of industrial civilisation) and reliant on an extensive infrastructure for its existence: transatlantic cables, datas centres and so on. There is not yet an illusion of immediacy; the simulation fails insofar as it appears mediated.

The significance of the simulation’s failure should not be underestimated. Even though the user cannot avoid apprehension of the program’s basic deception (that this is an indexical representation), we nevertheless act as though it is. The power of Google Earth resides in its representative properties; what awes us is that this is the world in its entirety, all that is known and knowable. Such an attitude is what psychoanalytic theory calls ‘fetishistic disavowal’ - central to any understanding of ideology today.

Google Earth ultimately relies on a series of mystifications which are both symptoms of postmodern scepticism and a precondition for the continuation of global civilisation.

First, it reflects actually-existing power relations. Even a powerful entity like Google must make decisions about which regions to prioritise with the latest and most high-definition imagery. It has stated that the key factor is population density, but it is practically inconceivable that relative importance to the global economy does not play a part.

These imbalances are especially acute when it comes to the 3D mapping: a 2018 blogpost announcing the latest updates did not feature a single city in the Global South and only one, Tunis, in Africa. This proposition that certain cities matter more to the established global system is not controversial. And yet the effect is to reproduce naturalised notions about which areas of the world matter: invariably the core, the former metropoles.

But this is perhaps less significant factor than the God’s-eye perspective inherent to Google Earth. Such a perspective impresses on us the true scale of the planet, allowing us to grasp long-haul flights and transcontinental journeys. The vastness of the Pacific. But this is a disengaged view from nowhere and, indeed, satellite imagery can be conceived as the emblematic technology of ‘mastery over the planet and of abstraction from any place on it’.

At one extreme of the zoom, the planet resolves into a small, luminous orb suspended in the centre of our screens against a backdrop of the Milky Way. The sense is almost pre-Copernican, theistic - but a the same time, decidedly Cartesian: it can be sent spinning at the click of a mouse. The subject acts decisively on the object, which figures as an entity primed for geoengineering.

This links to a further ‘affordance’ which recalls Arendt’s observation (1958) that it was ‘precisely when the immensity of available space on earth was discovered’ that the shrinkage of the globe began. There are no more terrestrial frontiers or mysteries of the horizon, tales of unknown shores and spectral landmasses.

The original whole earth image, Blue Marble, inspires appreciation of fragility - gratitude, humility. But the (global) history of humanity has been driven by very different impulses: exploration, conquest and brutal subjugation. And once everything on Earth has been measured, this attitude is just displaced onto the cosmos itself. No phenomenon is more indicative that the accelerating ‘billionaire space race’.

To aspiring world-historical figures such as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, the finitude of Google Earth is a frustration and a call to arms. The ongoing mapping of the Moon and Mars is a precursor to making of them staging posts in the quest to make humans a multi-planet species. These entrepreneurs are the would-be Pizarros of the twenty-first century; except rather than in thrall to the patronage of monarchs, it is governments, to the contrary, that rely increasingly on their private industrial apparatuses for space services.

And it is to these titans to whom millions look for hope: their grand visions promote faith in coming technological salvation, which is figured as always just around the corner: from self-driving cars and carbon capture through to Neuralink and the terraforming of exoplanets. But in calling for colonisation of other celestial bodies (worlds made for humans by humans) rather than directing all resources to mitigating catastrophe at home, they evince a kind of nihilism particular to advanced capitalism.

Beyond the obfuscatory nature of the program’s fundamental architecture, the more granular can also be steeped in dualistic thought - even when the professed purpose is to promote climate awareness. In 2021, for instance, Google Earth announced a major update to the software: a time-lapse feature that enables users to ‘take a step back’ by sliding between thirty-seven years of satellite imagery. As director Rebecca Moore put it in a blogpost:

‘With Timelapse in Google Earth, we have a clearer picture of our changing planet right at our fingertips — one that shows not just problems but also solutions, as well as mesmerisingly beautiful natural phenomena that unfold over decades.’

Among a set of features on the lauded ‘solutions’ was an invitation to ‘meet’ the Suruí people’ of Mato Grosso, Brazil, with whom Google Earth (under the auspices of Engine and Outreach, two of Moore’s initiatives) has been collaborating since 2009 to combat illegal logging. This partnership, bringing together computing might and indigenous knowledge, is a striking example of how the program can be used for practical ends.

On first seeing a satellite image of his homeland, Google informs us, the tribe’s leader, Chief Almir, was immediately struck by its power to ‘convey the importance of his tribe’s natural heritage’. And thanks to the application of earth observation technology to protect it, the ‘native peoples themselves will be able to benefit economically from the forest’. The incongruity of this assurance is remarkable insofar as it blithely reproduces the very logic which leads to deforestation to begin with.

Suffice to say, it cannot be separated from the propaganda element of Google’s public messaging. On some level, it reveals that corporate leaders feel a pressure to justify the technology. The program must be more than a neutral instrument, or Earth porn: a tool for good, a consciousness-raising platform. There is an optimistic discourse about the potential applications of Google’s satellite data to geoscience. Another project involves monitoring fishing vessels illegally entering protected waters. But when it comes to corporate mystification, Big Tech is the pinnacle, such is the distance between missions statements (connecting the world, organising its information, continually raising the bar of the customer experience…) and the underlying accumulation model.

But perhaps the supreme ideological gesture of Google Earth is how the planet appears so healthy: all is blue, green and gorgeous. The default is a pristine atmospheric state. Of course, even with the weather option enabled (which superimposes real-time data), there are limits to how far this virtual globe can represent the planet’s complex dynamism. Gaia is unrepresentable. But we can still imagine Google taking more active steps to promote ecological awareness. Perhaps a Google Atmosphere, which would simulate concentrations of greenhouse gases since the onset of industrialisation, the majority of which since 1980, and with no sign of peaking soon.

The backlash would of course be considerable: this would probably be condemned as ‘politicisation’ of an ‘objective’ platform. And so making the reality of climate change overt or somehow integral to the projection would be impossible for Google. It would make of the Earth something radically Other, to defamiliarise and, in a certain sense, renature. It is in this deadlock that we can discern the limits of any effort to render a digital globe removed from the domain of Chakrabarty’s global regime.

Google Earth as artwork

Perhaps, then, it is better to view Google Earth as a fundamentally aesthetic phenomenon. It is a work of extraordinary beauty, a composite of countless human and non-human contributors, whose dual nature (scientific/artistic) was dramatised in recent miniseries The Billion Dollar Code (2021), whose central drama revolves around a patent infringement case against Google. The fictionalised plaintiffs, idealistic hacker Juri Müller and rebellious art student Carsten Schlüter, met in a techno club in 90s Berlin and founded design agency ART.COM. And with the somewhat unwitting support of Deutsche Telekom, they created the first digital globe: Terra Vision.

The series stands out for a certain boldness in highlighting the malpractices and spin of Big Tech. The injustices of corporate power are starkly portrayed: in the end, might makes right. When Google executive Brian Anderson recalls in court his early excitement about the possibilities of the technology (erasing borders, enabling people to grasp interconnections), the viewer knows full well that he snitched the ideas from Juri during a night of excess at Burning Man.

But the jury finds no infringement, largely, we assume, due to Google’s lawyer presenting a slick slideshow laying out, in grossly simplified form, how Earth is based on different mathematical principles to Terra Vision. Meanwhile, Juri and Carsten must endure the spectacle of their own side’s witness befuddling the jury with specialist terminology and opaque explanations.

Side-by-side comparison from the series The Billion Dollar Code (2021).

But however much it runs against the grain in these ways, the series ends with a cliché: the old friends, not on speaking terms at the beginning of the lawsuit, reconcile. Here lies the feel-good ideology. What matters ultimately is not the money but the affect, the system can’t be changed.

Beyond highlighting the injustice wrought on start-ups by corporate behemoths, it also highlights how Google Earth can be seen as a spectacular outcome of a kind of technological hubris that emerged in Silicon Valley with the advent of worldwide connectivity. This attitude is reflective of a kind of fideism as old as the Enlightenment: unerring faith in the basic desirability of continual innovation, powered in our time by exponential growth in computing power. Even in the face of widespread democratic decay and extreme polarisation, the faithful in California remain ensconced in their starchitect-designed headquarters dreaming up projects like Metaverse.

This doctrine is realised in Google Earth and its close relative, Street View, which are both, like capitalism, totalising. Both seek, in theory if not yet in actuality, to cover everything. They must continually expand to stay relevant and so there must always be updates to the imagery itself (which in places like Dubai is always outdated), and to the attributes or ‘affordances’ of the platform.

So if Google Earth is a work of art, it could also be seen as an emanation in the sense of German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher. The program is a ‘visual manifestation of the scientific, cultural and political rationalisation of the earth within a simulated industrial culture’. We are fast approaching the limit-horizon of this planetary reserve, beyond which the capacity of critical systems to absorb stress is irreversibly destabilised, leading to unpredictable cascade effects.

The epistemic imperative of the Anthropocene is clear: to re-conceive ourselves as part of nature and internalise the impossibility of endless growth. But the predicament is a dastardly one. Google Earth is emblematic of an advanced scientific culture predicated on extreme rationalisation and objectification. And insofar as it reflects power relations and naturalises the ‘overview effect’, the program also reproduces dualistic thought. It should be seen as a ‘fetish object’ in the strict psychological sense, whereby a part is made to represent the whole.

Google promotes the tool as ‘the world’s most detailed globe’, but all that ultimately can be represented is the (idealised) surface. Seventy percent of the planet’s surface, the oceans, is glossed at best. And what we are left with is a profoundly anthropocentric globe in gamified form. The ineffable dynamism of the planet (tectonic activity, ocean currents, the swirling magma of the outer core) and its sheer temporal depth are impossible to integrate or domesticate. This presents a key difficulty: in spite of Google Earth’s unique capacity to incorporate temporality via regular updates and the Timelapse feature (in effect supplementing the spatial projections of old with a novel temporal dimension), the planet is nevertheless reified.

Tim Ingold (2000:242) writes of a paradox at the heart of modern cartography: that the more it aims to provide a comprehensive representation of the world around us, the less true to life it appears. Maps necessarily involve a certain fixity. And yet the world of our experience, by contrast, is ‘suspended in movement…continually coming into being as we - through our own movement - contribute to its formation.’

The cartographic project always fails; and in the case of Google Earth it does so precisely because of the collapse of the distinction between the two regimes of historicity Dipesh Chakrabarty elucidates, the very fact that our species has become a geological agent. We can no longer look at ‘nature’ as a wholly autonomous force. The natural events that Google Earth can only partially portray - storms, hurricanes, even earthquakes - are increasingly inseparable from our own actions. This is a profound challenge to what it means to be human. In Heidegger’s terms, a new and distinct mode of the disclosure of Being is upon us.

In this sense, Google Earth - despite its pretensions - is as ‘global’ in Dipesh Chakrabarty’s sense as was Martin Behaim’s Erdapfel. Both are fundamentally symptomatic of the quest to eliminate ambiguity and master the ‘external’ world. And although we can identify how this keeps us trapped in dualistic thought, it is almost impossible to think outside of this framework. Global industrial civilisation is predicated on knowing the relations between parts and the observer’s relative position to the whole. There is no straightforward undoing of this through thought. So the point is not so much to critique Google Earth itself, a spectacular achievement of science and information capitalism, but to engage the dialectic of the Enlightenment: the notion that, at this late stage in capitalist civilisation, it is more and more the objects that act on us.

Perhaps nothing dramatises this better than a forthcoming ‘black box’ for Earth on the plains of Tasmania. Its purpose it will be to record changes in the climate, and it is designed to outlast civilisation. The box could be seen as a scientific counterpart to the Golden Records sent out aboard the two Voyager spacecraft into interstellar space in 1977. But while the idea of sending intangible cultural heritage into the abyss is more or less intuitive, when it comes to the remote black box, things are more mysterious. Who are the recipients of this data? For whom are we recording? Lacan’s answer would be: the big Other, the symbolic order itself.